Fixing Your Flamingos: How to start writing your family history when you don't have all the answers

Have you written down any of the family history you’ve discovered? You’ve got generations of relatives added to your family tree with key documents proving important dates and places. You’ve done some difficult digging to uncover hidden truths about your ancestors, sorting fact from fiction with careful study. But have you told any of their stories in writing, preserving your carefully reasoned conclusions for future generations, or just to share with your contemporary cousins?

This can feel especially daunting when you’re not done with your research on a particular individual or family. But writing it all out is one of the best ways to find gaps in your research, flaws in your logic, information without sources, and new questions to ask yourself and your records.

The best thing to do is to just get started!! Choose a writing style or format and dive in. (You could write about how the generations of a family are linked, you could write research reports about how you determined the answers to specific research questions, you could write small vignettes of the family stories you know, you could write about someone’s military service or career, you could write full biographies of individual ancestors, the possibilities are endless!) You don’t even have to write your genealogy in order! (Insider secret: I didn’t write this blog post in the order you’re reading these paragraphs!) Start at the beginning, or with whatever piece of history interests you most. You can go back to rearrange, reformat, and fill in the gaps later, once you’ve got some momentum.

But then, you ask, how do I keep track of what I do and don’t have in my writing? My favorite tool for this is seriously so simple, and you can use it in any word processor more complex than MS Notepad. Microsoft Word, WordPad, OneNote, Evernote, AbiWord, and a whole host of others will all do nicely, or you could even adapt this method for handwritten manuscripts, if that’s your cup of tea. (I’m mostly a Google Docs gal myself.)

Flamingos. They’re the tool. That’s what I call all of the things in a piece of writing that I know I need to improve. Why? Because I set that text to fuchsia, or magenta, or some other vibrant color. This allows me to easily scan pages of text later to go back to fill in details or make other necessary edits.

When I was writing essays and papers in high school and college, I would always start writing somewhere in the middle, with whatever point I was most passionate about making, wherever I had a spark of inspiration. Then I’d go back to fill in relevant statistics and clean up rough wording, then I’d usually write the intros and the conclusions last.

In genealogical writing, I tend to mostly go in chronological order, but there are often gaps in the information. Sometimes I don’t have all of the facts yet because I’m not done with my research, but I want to make sure I write out all of the logic behind a particular conclusion or finding before I lose my train of thought. Sometimes I’m pretty sure an original record is going to prove something, but I can’t say that for sure or I can’t write the full citation yet because I’m waiting for a copy of said record to arrive in the mail, which can take quite some time. Sometimes I’m tired and I just want to work on the easy parts. Sometimes I just don’t like how something is worded but I haven’t come up with anything better. These gaps and flaws in my work become an entire flamboyance of flamingos.

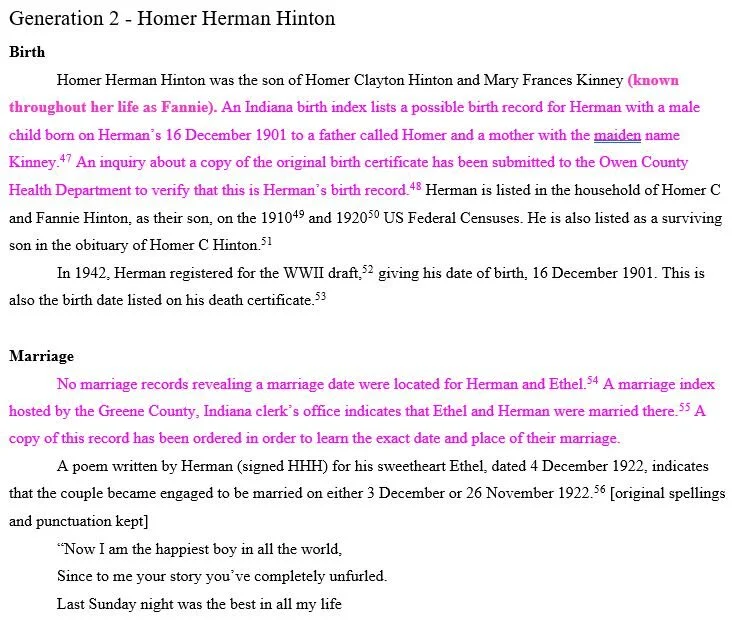

For example, below are two sections of a research report about the Hintons, my paternal grandmother’s paternal line. I wrote most of this 22-page report while I was waiting for my great-grandfather’s birth and marriage certificates to come in the mail from county archives. I wrote out what I could prove at the time, and set the text I knew I would need to edit to bright pink.

Once I received the documents, the flamingos jumped off the page, making it so easy to go back to update the report with more conclusive evidence and specific details, and then set the final text back to black. (“Black, black; Black; I go back to; I go back to…” Name that tune, anyone? No? Okay, that’s fine.)

This strategy pairs incredibly well with a research log, like the one I have available here.

I take thorough notes in my research log to keep track of what’s in the records I find, as well as many of my thoughts, ideas, comparisons, questions, and conclusions. I often paste these notes directly into my writing, with just a bit of cleanup for the reader. And then it’s a cinch to add in the citations from my research log as either endnotes or footnotes. The log does about half of the writing for me when I use it diligently.

Genealogical writing doesn’t have to be hard.

It can feel daunting to try to pull together paragraphs organizing all of the facts that are so conveniently laid out in your family tree. But what about the personal stories of your ancestors that go beyond the dates and places? What about the details of how you know that your great-grandparents ran away together because their families didn’t approve of the marriage? Or the details of how you finally found the proof that your ancestor fought for the Union in the American Civil War, despite being born in the South? A healthy family tree is a vital database, but the diagram can’t tell the whole story.

So go on and start writing it down. Write your ancestors’ stories or pieces of your own (because your life is future family history!). Create flamingos wherever you don’t quite know what to say. Then you can easily go back to fix your flamingos one at a time, as you have the time and information.*

*Sometimes—unfortunately— you’ll never get all the facts. Some things just weren’t written down in certain time periods and populations. Some records were destroyed by natural disasters or war and their details are lost to time. Here, it’s totally okay to explain your best guesses at missing information. But where you haven’t yet conducted a reasonably exhaustive search, make a flamingo, and fix it with the information you have when your search is complete.

Want more help and personal encouragement?

If you’re still not sure where to get started, or if you’d like some help culling your personal flamboyance of flamingos, that’s absolutely something I can help with in one-on-one coaching! On top of my degree in family history research, I studied journalism at the college level and I used to work as a copy editor for a history magazine, so I would love to chat about your genealogical writing!