National Coming Out Day: Remembering Those Who Were Never Able to Come Out

National What Now?

On 11 October 1987, around 750,000 people marched on Washington, D.C. in the Second National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights, also known as "The Great March." (The first was held 14 October 1979.) A year later, the first National Coming Out Day was celebrated to mark the anniversary. Within two years, this queer holiday was celebrated in all 50 states.

Consider: Could any of your ancestors or relatives have attended either of these marches? Millions of Americans could say yes whether they know it or not!

The act of “coming out” (aka coming out of the closet) is when an LGBTQ+ person voluntarily discloses their sexual orientation and/or gender identity. This can include private disclosure to individual friends and family members, and/or a full public disclosure. Often seen as a right of passage in the queer community, this allows a queer person to begin to live more authentically, being seen more fully and accurately by others. Queer people experience a wide range of emotions around coming out, as it can drastically improve their lives—especially regarding their mental health, but they many also risk backlash due to negative reactions from others, perhaps jeopardizing close personal relationships, job security, personal safety, and more.

National Coming Out Day is rooted in the knowledge that we should celebrate who we are to achieve a more loving and inclusive world. Homophobia, transphobia, and other limiting and oppressive beliefs thrive in silence and ignorance. Once people realize that they have loved ones who are a part of the queer community, they are far less likely to maintain queerphobic beliefs and practices, like using slurs or other derogatory language.

Coming out is an intensely personal decision that queer individuals do not make lightly. It is not always safe for a person to come out. There is no shame in remaining in the closet, and it does not detract from a person’s queer identity. It is imperative that queer individuals are allowed to come out on their own terms and in their own time. While queer people today in much of the world enjoy freedoms, rights, and support the LGBTQ+ community did not receive in the past, there are many places and circumstances (even within the most free and accepting countries and communities!) where queer people do not enjoy these benefits.

And then we look to our ancestors…

Until as recently as 1962, all 50 US states criminalized some level of same-sex sexual activity. Queer people of all sorts have always existed, but for much of history, they were forced to hide much of themselves for physical safety, social and familial acceptance, and legality. Take a moment to really try to put yourself in their shoes. Today, in addition to celebrating the queer people in our lives—especially those just now coming out—let’s pause for a moment to remember and honor our queer ancestors who never had the privilege of coming out at all.

Outing your ancestors or telling their story?

Genealogists don't hesitate to reveal illegitimate births, tragedies, and other personal details of their cisgender heterosexual ancestors' lives. So why do we hide our LGBTQ+ ancestors? Many of our ancestors couldn't openly be themselves during their lives, but we can respectfully honor their struggles and identities now.

“When coming across a person or a record that gives a hint towards a person’s homosexuality it is especially important to take a closer look and not shy away from discovering more. Telling truthful stories means moving away from the notion that homosexuality tarnishes a person’s character. Revealing the truths of the past, to tell stories openly without judgment, about the struggles they endured will honor our ancestors and will give us a deeper understanding.”

—Stewart Blandón Traiman

“Bias, ego, ideology, patronage, prejudice, pride, or shame cannot shape our decisions as we appraise our evidence. To do so is to warp reality and deny ourselves the understanding of the past that is, after all, the reason for our labor.”

—Elizabeth Shown Mills

How would you know if an ancestor was LGBTQ?

Note: Of course, many straight cisgender individuals have found themselves in many of the circumstances outlined here. These are simply clues that could be combined with other information and records to indicate an LGBTQ+ identity/person. Just like with any other fact about a person, a genealogist should limit their assumptions and seek correlating evidence before claiming to know anything for sure.

Companion/Roommate

If your ancestor never married (or if a marriage ended) and they lived with the same person of their own gender for most of their life, this person could have been a romantic partner. Until very recently, they would not have been listed together in census records as spouses. They may have been listed as two heads of the same household, boarders, lodgers, or partners.

Gayborhoods

Where did your ancestor live? Where, specifically, within that city?

The US military used to drop off Other than Honorably discharged men at the port of San Francisco. Disgraced, many stayed and found community among one another. Communities like this formed in places like The Castro, San Francisco; Boystown, Chicago; West Village, New York; Le Village, Montreal; Schöneberg, Berlin; Le Marais, Paris; and so many more!

Profession

The gay hairdresser stereotype actually has some historical origins. Even today, many places offer LGBTQ+ people little to no employment protection. As a means of survival, many queer people have pursued professions where they could be self-employed, and/or where their skills could easily be taken to a new city if they needed to leave an area. Florists and nurses are needed everywhere. The arts have also been historically welcoming to the LGBTQ+ community.

Read Between the Lines

An obituary may refer to a "longtime partner," or an "intimate/devoted friend" of the same gender. An administrative Blue Discharge from the military was often used to oust gay servicemembers. Context is essential in understanding historical documents. Take the time to research words or phrases that are unfamiliar or unclear to you. This will make a world of difference in all of your research.

Recording Transgender Individuals in Your Family Tree

Deadname - the name that a transgender person was given at birth and no longer uses upon transitioning. Deadnames can be stored in personal notes as they may be necessary to locate records created prior to a person's transition. They should not be shared unnecessarily. This can be traumatic for a transgender person. Always use a person's real name. The name a transgender person has chosen to use after their transition is their real name. Genealogists almost always use the names people were given at birth, such as maiden names, to clearly identify individuals consistently throughout their lives. This is a very important exception to this rule!

Only a short note about transition is needed in a written family history, to explain the transition of name and gender found in records, to clarify/prove that the research is correct and the records before and after transition refer to the same and correct individual. "Assigned [male or female] at birth" is the correct way to refer to a transgender or nonbinary person's experience, rather than hurtful verbiage like "was born a man" or "is biologically female." Always use the correct pronouns when writing about a transgender person, whether you are describing their life before or after their transition.

Some pre-transition records will never change and are genealogically important. Some records, like a birth certificate, can sometimes be changed. Transgender and gender expansive people may be recorded in different ways at different times throughout their lives. In many ways, this is similar to researching adoptees or women. Genealogists overcome conflicting or confusing evidence all the time.

You can do this with love, without causing harm. Understanding the stories of the people in your family tree is the whole point of family history research.

Ask living trans people how they personally would like to be included in your family history and what parts of their story they would like to have recorded or shared. Transgender people are not a monolith and some individuals may have different preferences or wishes regarding their own lived experiences.

LGBTQ+ Genealogical Records

There are some sources that are unique to LGBTQ+ research and some hints in standard records that you might miss if you’re not careful.

LGBTQ+ Periodicals

For decades before the Internet, printed periodicals were an important source of information for the LGBTQ+ community. Zines, magazines, newspapers, and newsletters notified us about news, meetings, events, demonstrations, queer-friendly businesses, and more. They contain first-hand accounts of events, interviews, photographs, and much more that can be valuable to genealogists and other historians.

Vital Records

Birth: Recently, transgender and intersex individuals have been allowed to change the sex listed on their birth certificate. Historically, some birth certificates might indicate a visibly intersex child with notations like “Unclear,” “H,” “Hermaphrodite” (no longer an appropriate medical term), etc.

Marriage: Check local laws to verify when same sex marriages or civil unions became legally recognized in places you're researching, if they are.

Death: Heartbreakingly, many queer folks have been lost to the AIDS epidemic as well as hate crimes.

Obituaries

An obituary may refer to a "longtime partner," or an "intimate/devoted friend" of the same gender. Obituaries usually only mention close family, so this is especially significant.

A gay man's obituary may highlight that "he never married" or was a "longtime bachelor."

More recently, obituaries may openly list queer spouses or partners, or give other enlightening details without shame or coded language.

Census Records

If your ancestor never married (or if a marriage ended) and they lived with the same person of their own gender for most of their life, this person could have been a romantic partner.

Before the 21st century, they would not have been listed together in census records as spouses. They may have been listed as two heads of the same household, boarders, lodgers, or partners.

A census could also reveal that an ancestor lived in a traditionally gay neighborhood like The Castro in San Francisco or New York’s West Village.

Police and Prison Records

When homosexual relationships were illegal, an ancestor could have been arrested in a raid of a gay club, or for "cottaging," "tea rooming," “sodomy,” or other gay "offenses." Records of such arrests or imprisonment can be found in criminal databases or in newspapers.

Military Records

Gay men have served in the US military since the American Revolution, with lesbian service since at least World War I. The US National Archives holds thousands of pages of documents related to US policy towards queer people in the military. An administrative Blue Discharge from the military was historically used to oust gay servicemembers in the US (until the repeal of “Don’t Ask Don’t Tell” in December 2010). After WWII, they were often left at the port of San Francisco, starting the city's long legacy of LGBTQ+ culture and acceptance.

Personal Effects

Letters, photos, journals, literature, and other personal belongings left behind by our ancestors can provide a wealth of insights and clues about many parts of their lives which may not have been recorded in official documents, or which may not have been passed down via oral family history.

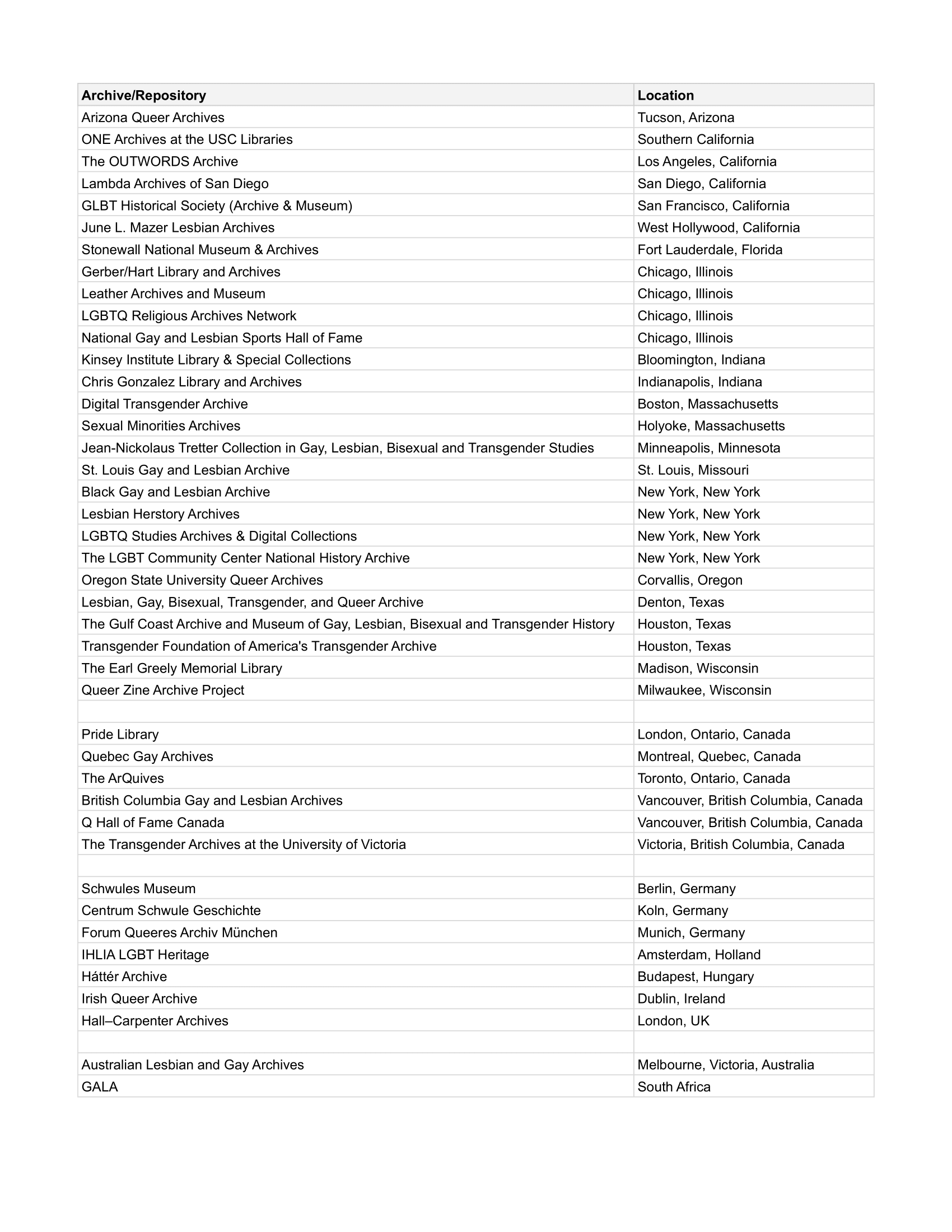

Repositories and Archives for LGBTQ+ Research

Around the world, various organizations and institutions have taken it upon themselves to record and preserve LGBTQ+ History, heritage, and records. These repositories contain an abundance of information about the gay liberation movement, queer people, queer experiences, and much more. They contain original artifacts and documents like magazines, newspapers, photographs, letters, memorabilia, etc. The following list is not exhaustive, but it contains some of the largest resources across the world. Many of these repositories have some of their materials available online, so check them out!

Additionally, there are LGBTQ-specific collections at many other libraries, museums, and other repositories of all kinds. And of course, LGBTQ+ people are regular people who are found in all of the standard record collections you’re already using as a genealogist or historian.

The list below is a great starting point.

Final Thoughts

LGBTQ+ people have always been a part of our societies and our families. The historical inability of many to make these parts of themselves known publicly does not make them any less real, less valid, or less important (just as with those living in the closet today). Often we cannot know everything about a person through research, even when that research is thorough, careful, and stripped of as much bias as possible. This is the way with much of history; without surviving personal writings or eyewitness testimony, we often cannot know with 100% certainty much about the events that transpired in the past. But we can make educated inferences and honor those we are researching by being open to possibilities without making moral judgements or unfair assumptions.

Thanks for being here with me as we consider our past and reexamine our families through a variety of lenses to try to understand one another with the love and compassion our ancestors (and all people) deserve. I hope you feel more empowered as a queer person or as an ally to effectively research and tell the stories of your family. Remember that pride in our ancestors—especially the marginalized ones—lasts all year.